Although just nearing the end of his teenage years, Kodak Black has been accruing good faith within his community for half a decade now. 2013’s Project Baby, his stunning debut mixtape, is an unflinching coming of age story set in Pompano Beach, Florida’s Golden Acres – a government-subsidized housing project that has been neglected for decades by Broward County. Two years prior, a remix of Wale’s “Ambition” had already seen the 14 year old kid earnestly penning bars such as: “I’m just livin’ with patience, dedication and greatness/how can I be good when the hood so-so my validation?” By the time Drake tapped Kodak for his first taste of commercial exposure, “No Flockin,” a fiery anti-drug, pro-getting-money-by-any-means PSA, was already a cult classic. With a slew of other viral hits under his belt before he could even legally enter a club (“SKRT”; “Skrilla”; “Like Dat”), he began to fill the void left by Chief Keef’s more reclusive tendencies.

However, just weeks prior to that fateful Drake cosign in October 2015, Kodak was fighting charges of robbery, battery and false imprisonment of a child. Subsequently, towards the end of the next summer, the 19 year old was arrested two more times in the span of one month, for charges such as possession of a weapon by a convicted felon and armed robbery. And amidst those most recent proceedings, an additional, gravely serious offense came to light: sexual assault charges stemming from an incident following Black’s performance at “Treasure City” in Florence, South Carolina.

For many of his core fans, Kodak exemplifies what it means to remain loyal to one’s community. The bond between Kodak and his home was the inspiration for his first two projects, and the aforementioned good faith is a byproduct of this honesty and authenticity. This genuine connection has created a trust that doesn’t seem to erode all that easily, persisting through the series of lewd acts Kodak chose to engage in following the sexual assault accusations. At one point, he teased an early version of his lead single, “Tunnel Vision,” in which he can be heard rapping, “I get any girl I want, I don’t gotta rape.” (A since altered version of this track is now the #6 song in the country).

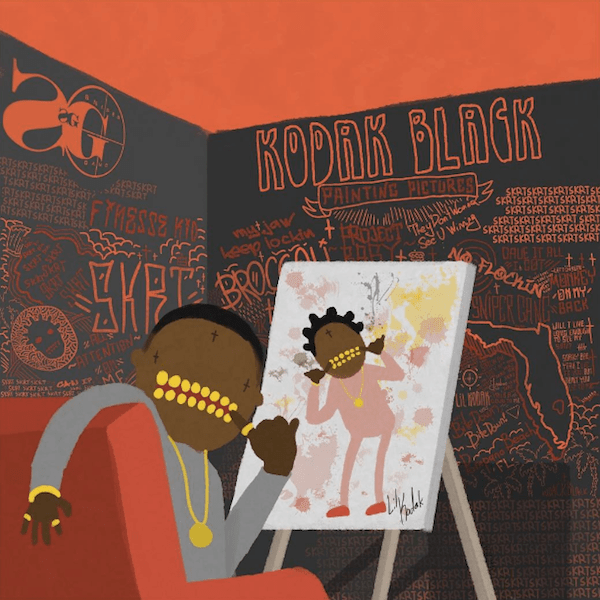

This article, written by Antonia Farzan, attempts to place Kodak’s upbringing and newfound fame in perspective – that is, in a context that not only holds Kodak accountable for his own actions, but also considers the pre-existing systemic issues that paint the world he inhabits. Because, despite his actions, his fanbase hasn’t relented and his major label debut, Painting Pictures, is set to move 47K this first week.

2015’s Institution turned to look at the fallout of being raised as a self-proclaimed “project baby.” Last year’s Lil Big Pac was centered around his previous incarceration and layered with spiritual undertones. This unflinching self-reflection is more elusive than ever before on Painting Pictures. Which is odd, considering last month’s loosie, “My Time” (a song that has inexplicably flown under the radar), sees him deliver sobering lyrics such as:

I’m tryin’ not to get locked up back again

Had to take a lot of losses just to win

I was young, jumped in that water, been swimmin’ ever since

Then I drowned, I never noticed how deep that I went

This level of self-awareness can consistently be found in Kodak’s own music (Project Baby’s “Never Imagine”; Heart of The Project’s “Better Days”; Institution’s “This Life”; Lil Big Pac’s “Can I”). Just a cursory glance at the rapper’s discography prior to his arrests in 2016 would have painted the image of a wild, but grounded street poet, with the ambitions of a Hot Boys-era Lil Wayne and the authority of prime-Lil Boosie. Expertly navigating between raw tales of perseverance and raunchy, drug-addled bangers, Kodak often showed range and nuance beyond his years. But on this debut, the emotional arcs often times takes a backseat to the artist toying with his various hit-making templates; as a result, progression stalls and his artistic shortcomings are all the more apparent.

When it comes to the hooks, Kodak is sharper than ever, but the verses have never felt more expendable. For most of the project, the storyteller who penned Lil Big Pac’s “Letter,” capable of embodying multiple perspectives, takes a backseat to the songwriter with fast-developing pop-sensibilities. Case in point, “Tunnel Vision,” Kodak’s biggest hit to date, sports verses that are, for all intents and purposes, merely decorative. In this regard, the album feels uneven. The soul searching feels tempered and Kodak’s previously documented insecurities appear to be under lock and key. The Future-assisted standout, “Conscience,” is an emotive breath of fresh air in contrast to the largely lackadaisical soundscape. Similarly, the Jeezy-assisted “Feeling Like,” boasts a passionate verse from an otherwise subdued Kodak. With a rabid fanbase eager to forgive, forget and move on, a hardware dump meant to shuffle through a series of carefully crafted potential hits probably felt like the safe move.

The production is handled by a mix of trusted in-house talents (Dubba-AA; C-ClipBeatz) and more recently formed relationships with industry heavyweights (Metro Boomin; Mike-WiLL Made It; Ben Billions) alike. Bright, contagious beats help Kodak tap into fresh vibes, but the darker, more meditative bangers we’ve come to expect are still there punctuate the bubbly soundscape. Due to this purposeful array of sounds, the accompanying mood fluctuates at an almost dizzying rate. Tracks like “Up in Here,” a frantic panic attack on wax, are nestled between the more colorful backdrop of the Bun B-assisted “Candy Paint” or the self-assured boasts of “U Ain’t Never.”

Although still very much a developing vocalist, the Pompano Beach rapper possess great control over his distinct drawl, getting the most out of his natural dialect with every turn of phrase. Frequently opting for soulful singalongs, Black’s greatest strength on this album is his ear for melody and the bluesy underpinnings that anchor his songwriting. He seems to make a conscious effort to double down on his viability as a pop star and, in that regard, he crafts some of his most refined anthems to date (“Tunnel Vision”; “Patty Cake”; “Twenty 8”). “Patty Cake,” a menacingly fresh take on an age-old nursery rhyme, is the sort of brilliant jingle that makes Kodak such an undeniable figure in the current rap scene. “Off the land,” Kodak’s first collaboration with YSL producer, Wheezy, is a delicate, infectious bop that sees an unbothered Kodak declaring: “I don’t make that bubblegum music I spit that real shit.” Wheezy’s airy instrumentation proves to be a surprisingly seamless fit for a rapper as melodically inclined as Kodak. (The following track, another Wheezy beat that marks his first collaboration with Young Thug, feels like it would’ve found a more fitting home on one of Thug’s own projects).

Where the death of his grandfather and the birth of his daughter led to the moving stream of confessionals found on last year’s “News or Something (Remix),” such reflection is almost strategically stricken from this album’s hour-long runtime. For the most part, the duality that once made Kodak a gripping lyricist is hard to pinpoint. However, that’s not to say it is completely absent. “A mouth full of gold teeth, they think a n**** dumb/I got a head full of dreads, think a n**** illiterate” he scoffs on the A Boogie Wit Da Hoodie assisted “Reminiscing.” “Coolin and Booted” sees him reminding us: “youngest n**** in the game/I’m fourteen when I caught a case/I was fifteen with a thirty-eight.” And on the intro, “Day For Day,” he outright raps: “I was already sentenced before I came up out the womb/Streets done already sentenced me, before no cracker could.” Amidst the aloof aesthetic, he manages to sneak in the very real context that influences his every decision on and off wax. Although scattered, the pieces are there to together understand Kodak’s underlying motivation behind this project: painting the overarching image of a man sentenced from birth.

So, yes, he never fully pivots into self-reflection, but it’s hard to imagine how the public would have reacted had he done so. At one point on “Corrlinks and JPay,” an understated ballad anchored by his time in prison, he lets slip his most honest – and, unfortunately, most telling – line on the album: “I put my trust in that bitch, that hoe let me down.”

Yikes.

But the question remains: how good would Black’s debut, Painting Pictures, have to be for you to move on from the sexual assault charges? The typical response to one’s understandable hesitation with supporting the work of a problematic artist is always something along the lines of: “separate the art from the artist.” But in a genre so co-dependent on “authenticity,” it becomes increasingly difficult to do so. And it’s hard to blame someone who’s simply not interested at this point.

In the end, irrespective of your opinion on Kodak Black, Painting Pictures is a youthful, disarmingly soulful debut that ultimately suffers from teasing introspection that never fully materializes.

Notable Tracks: Up In Here, Patty Cake, Corrlinks and JPay, Off The Land

Honorable Mentions: Candy Paint (ft. Bun B), Twenty 8, Conscience (ft. Future)